Minnesota’s water governance is considered some of the best in the country, and we’ve been hearing a lot about it since we began a year-long project in March 2021 to assess governance across six states and tribal nations within them: Groundwater Governance in the Great Lakes States. Others yearn for the depth and breadth of laws, programs, and especially the stable funding that Minnesota has established.

Minnesota created the State Board of Health in the late 1800s to address clean drinking water and sanitation concerns. The drought crisis of the 1930s Dust Bowl led to the creation of water-use permits and the first sewage board, the Water Pollution Control Board (now the MPCA), and the 1960s saw renewed efforts as Minnesota and the country were waking up to widespread environmental degradation. At that juncture, the state addressed ways to clean up water pollution from sewage treatment plants, figure out how to reduce damages from flooding, and take action for clean and safe drinking water from public water supplies.

One authority? Or more?

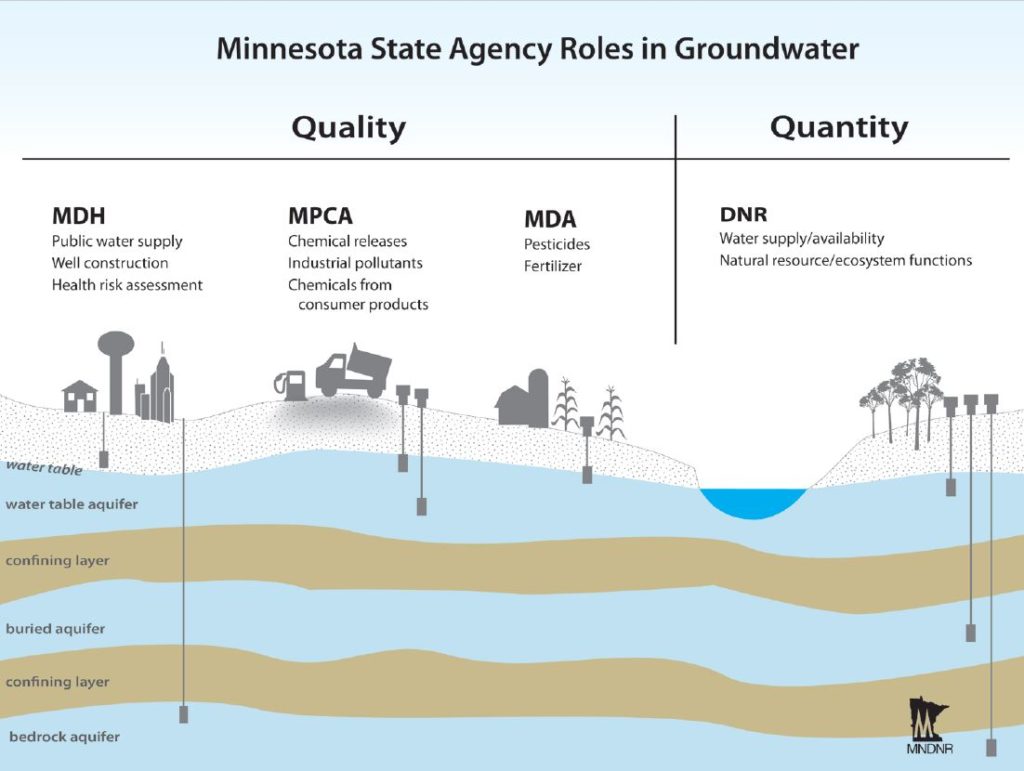

In 1969, Republican Gov. Harold LeVander asked staffer David Durenberger* to envision ways to organize Minnesota’s environmental laws and programs. Was one water management authority better than multiple agencies? Many argued (and continue to this day) that merging authorities and funding would simplify and reduce overall costs of water governance. I disagree. Minnesota’s approach is built on the expertise of each entity of state government, and that expertise leads to rules, programs, and funding that directly connect to the overall goals of Minnesota’s water governance laws. A merged water governance authority would weaken the voice of specific expertise, at the expense of reducing costs or regulations.

For example, safe drinking water regulations and authority belongs to the Minnesota Department of Health, home of public health protection expertise. If merged, the expertise applied on water use and impacts on water quantity (currently at the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources) could override public health expertise leading to increased health risks. Minnesota’s separate and equal water governance model assures checks and balances when faced with competing interests for water decisions.

Patchwork governance in practice

This patchwork governance model does require vigilant guardianship by the legislature, state government leaders, Minnesotans and skilled nonprofit organizations like Freshwater. Our 2019 Trajectory Report provided insightful recommendations about the past, present, and future of the Clean Water Fund—the constitutionally dedicated fund to support action for clean and safe water across Minnesota. The state agencies and the Clean Water Council have implemented many of those Freshwater-led recommendations and Freshwater’s Jen Kader currently holds the nonprofit seat on the Clean Water Council, which gives Freshwater a strong voice in decisions about the Clean Water Fund spending.

As for me, I’ve been a part of state water governance since 1978, when I began working for DNR, until 2019, when I retired from the MPCA. The legislature has continually reviewed water governance in Minnesota, seeking to improve it. Over the years, many studies, committees, and working groups have asked the same questions raised by Gov. LeVander: Is one water agency better? Each time, Minnesota made organizational adjustments to reduce the risk of siloed governance and redundancies but kept its separate water authorities, respecting the differing agency expertise that exists in the fields of agriculture, natural resources, public health, pollution control, and local implementation of soil and water conservation. As a result, Minnesota maintains its reputation as one of the top states for enacting laws, rules, programs, and funding that protect and restore freshwater resources.

*(Dave Durenberger went on to serve as one of Minnesota’s two U.S. senators from 1978–1995.)