by Dick Gray

The bluebirds may be the first of the migrating birds to show up in the Twin Cities in the springtime and many of the human wintertime snowbirds have returned early as well, but the true harbinger of spring is when the ice goes out from Lake Minnetonka.

Lake Minnetonka is no stranger to drastic changes in its makeup, appearance and use. It was born in glacial times and was profoundly altered as the remnants of four major ice sheets that advanced and retreated over Minnesota ground, scoured and scraped the landscape over which they traversed.

These glacial ice sheets have been named the Nebraskan, Kansan, Illinoian and Wisconsin and they originated from 3 different glacial centers: the Labradorian originating from southern Quebec, the Patrician from southwest of Hudson Bay; and the Keewatin from northwest of Hudson Bay. Glacial ice, as it melted and retreated, dropped its “drift” or ground-up debris, which helped to identify their origin and pathways traveled.

The Wisconsin ice sheet or glacial stage is Minnesota’s youngest glacier to pass over its territory some 11,000 years ago. It was comprised of four lobes or tongues of ice, leaving vast quantities of glacial drift as they finally melted and retreated. The four lobes are identified as the Iowan, Tazewell, Cary and Mankato by their particular drifts. The last major advance of the Wisconsin state was a sub-lobe of the Mankato sub-stage which reached as far south as Des Moines, Iowa.

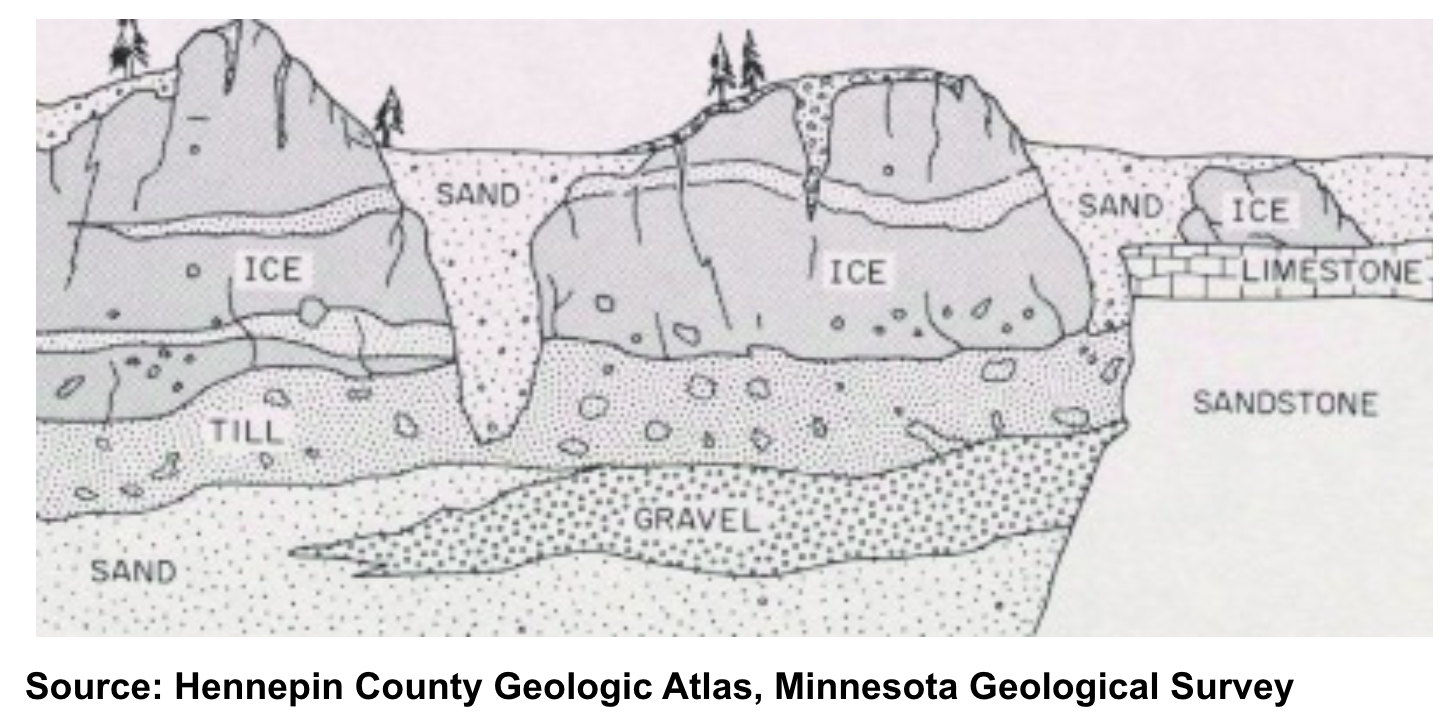

Lake Minnetonka was created by the main Wisconsin Glacier (or a lobe of it). As it moved across the lake’s territory, it gouged further material from previous glacial activity and then dropped large and irregular blocks of ice – land-locked icebergs – full of different drift of different chemical compositions as it retreated.

The huge dirty bodies of tightly compressed crystals of glacial ice melted over a period of 2,000 years or so. The drift dropped out and became the soil of the lakes and the land around them. The uneven shapes of these blocks of ice determined the basins of the lakes, the depths of lake beds, the irregularity of shorelines, presence of channels and islands and left a connected major imprint of 15 interconnected ice-block lakes that are labeled Lake Minnetonka.

It is because of this tangled glacial history that Lake Minnetonka is composed of three different kinds of water (hard, sort of hard and sort of soft) that made it an ideal study area for establishing the Gray Freshwater Center and the Freshwater Society at their present location in Navarre.

The glacial history also defines when and where the ice first freezes and when and where the ice first goes out, depending upon the type and amount of special glacial drift and its chemical composition.

Types of fish, the specific gravity of the water, clarity, leaf colors in the fall and the time of ice-out in the spring – parts of the lake losing their ice at different times – are determined primarily by the drift and where it came from.

Lake Minnetonka holds many secrets.

A major source of data for this article came from a 50-year-old Bulletin #35, authored by Dr. James H. Zumberge, published by the Minnesota Geological Survey and supported by Dr. George M. Schwartz, the former director of the Minnesota Geological Survey. The bulletin was titled “The Lakes of Minnesota, Their Origin and Classification.”

At this time, I also wish to recognize the teachings and support of Dr. George A. Thiel, sedimentologist; Dr. John W. Gruner, mineralogist, Dr. Herbert E. Wright, Jr., glacialogist; Dr. George R. Downs, petroleum geologist; and other faculty members of the Geology Department of the University of Minnesota.