I felt a bit like Sherlock Holmes when Konrad Schmidt, retired DNR Fisheries biologist, contacted me about when the last known contact took place between two fish populations — the rainbow darters in Lake Phalen and their river cousins. Genetic drift had occurred between the two disjoint populations but the question he posed to me was about how much time had elapsed. Naturally, you ask a glacial geologist this question.

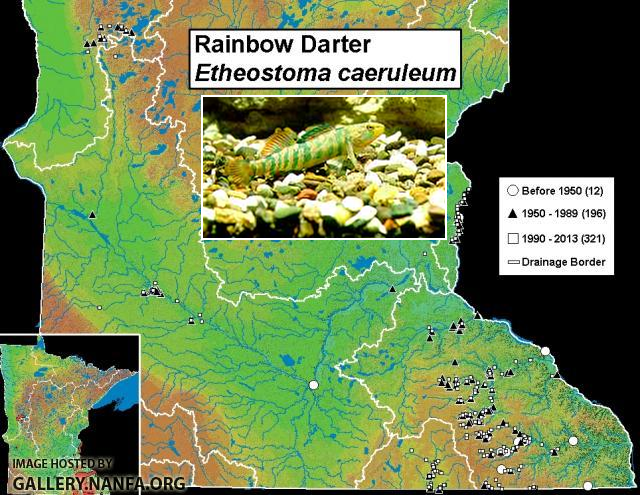

The rainbow darter (Etheostoma caeruleum) is a bottom-dweller that prefers fast, turbulent waters found in shallow rocky riffles in clear-water streams. They are common in southeastern Minnesota streams and small rivers, like the Cannon, Zumbro, Root, and Cedar. It is very odd to find them in the shallow water of Lake Phalen in Ramsey County. There is currently not even a path for them to get from a rocky, clear-water stream to the lake.

The stream from Lake Phalen dives into storm sewers, even crossing under I-94 before spilling into the Mississippi. One might think the genetic drift that occurred between the disjoint populations was caused by the build-up of the St. Paul urban area and separation of the Rondo neighborhood. But this drift needed deep time — geologic time.

So when was the last time that the lake was connected to the Mississippi by true riverine habitat and what event could have separated them? Let’s talk about waterfalls.

When the last, vast meltwater lake drained from the retreating ice sheet around 13,400 years ago, a big river flowed through the state and a bank-to-bank waterfall formed in the vicinity of downtown St. Paul. Use the Wabasha Bridge to imagine the span of the waterfall, which was located near the St. Paul downtown airport. It retreated rapidly upstream because of turbulence at its base that undercut the rock holding up the falls.

When the waterfall retreated past the creek that entered from Lake Phalen, it created a tributary waterfall in Swede Hollow. This new waterfall on the creek is the prime suspect in separating the Mississippi River rainbow darter population from the Lake Phalen one. The darters just couldn’t navigate the falls. Mr. Schmidt published a scholarly article that concluded the disjoint distribution was consistent with late Pleistocene and recent changes in the course and characteristics of the middle and lower Mississippi River.

The stories of fish — spreading to new areas and being isolated — can tell us a lot about the history of rivers and lakes. This story turns out to have had a natural cause, but every time we dig a ditch or connect a lake or wetland, we are opening the door to movement of species, potentially altering not only the fish populations, but entire aquatic ecosystems.

The stories of fish — spreading to new areas and being isolated — can tell us a lot about the history of rivers and lakes. This story turns out to have had a natural cause, but every time we dig a ditch or connect a lake or wetland, we are opening the door to movement of species, potentially altering not only the fish populations, but entire aquatic ecosystems.

If you want to hear stories of this played out on a grand scale — a Great Lakes and even global scale — come hear author and journalist Dan Egan speak about his recent book, The Death and Life of the Great Lakes. We are hosting Mr. Egan on April 25 in St. Paul and May 24 in Duluth as part of our Moos Family Lecture Series.

If you want to hear stories of this played out on a grand scale — a Great Lakes and even global scale — come hear author and journalist Dan Egan speak about his recent book, The Death and Life of the Great Lakes. We are hosting Mr. Egan on April 25 in St. Paul and May 24 in Duluth as part of our Moos Family Lecture Series.

— Carrie Jennings, research and policy director