At the municipal level, governments may have specific regulations regarding groundwater extraction, particularly for municipal water supply purposes. These can include building and construction codes outlining requirements for well construction and maintenance within city or town boundaries. This can also include land-use planning, where decisions related to economic development and infrastructure can impact groundwater resources. Most local governments plan their land use and infrastructure needs every 10 years in a comprehensive planning document and use these plans to guide interim decisions until the plan is updated. In the absence of federal, state or county oversight, a local government can still create a structure that values and protects its groundwater.

Local government units (LGUs) include regional, county, and hyper-local governments and may also be referred to as municipal governments, which include cities and townships. LGUs may also contain nested jurisdictions; a piece of land may be under the jurisdiction of the hyper-local township or municipality, and under the jurisdiction of the local county, and may also be part of a special district government. Because of the varied nature, size, and terms used for LGUs, work at the local level is complex and can be confusing.

At the county and regional level, authorities may be involved in managing groundwater, particularly in states where groundwater management districts are established. Counties can influence groundwater use indirectly through zoning and land-use regulations, which can impact the location and amount of groundwater extraction. Counties may enact ordinances that further regulate groundwater use, particularly in areas facing scarcity or contamination issues. For example, Eau Claire County, Wisconsin, has a groundwater advisory committee that oversees the management of groundwater resources. Two cities and eight counties in Minnesota have well management programs, with authority delegated from the State.

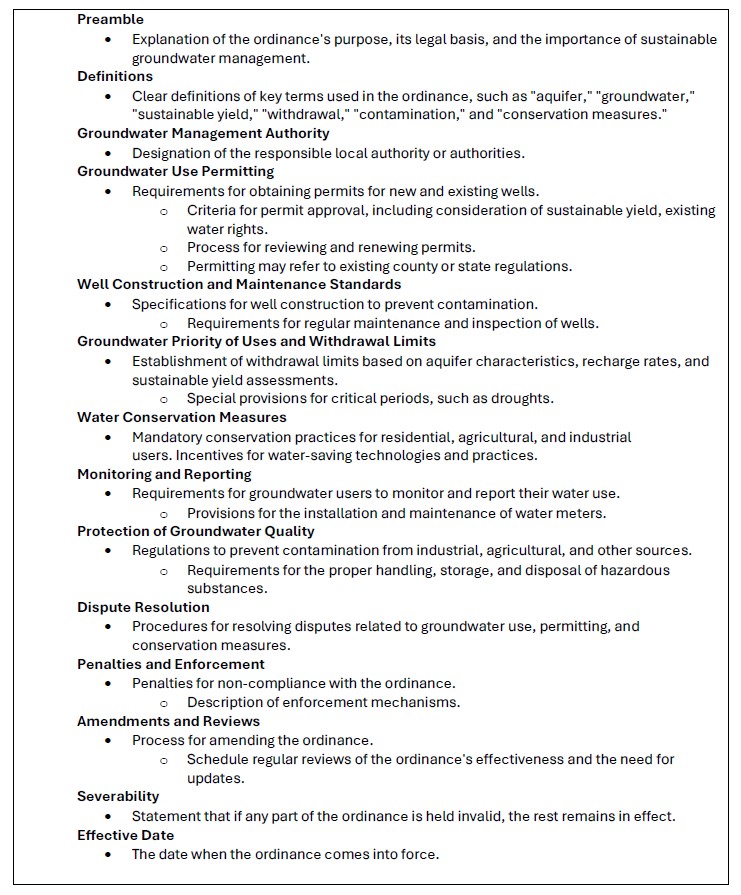

Model groundwater ordinance

Given the importance of groundwater for domestic supply (private and municipal wells), agriculture, industry, and the protection of natural resources, an ordinance should be designed to ensure sustainable use and protection of groundwater-supported ecosystems. Drafting a model groundwater ordinance for a cluster of municipalities involves creating a comprehensive document that addresses the specific groundwater management needs and challenges of these areas and their specific aquifer. The framework can be adapted to the particular conditions and needs of specific areas. The involvement of local stakeholders, including residents, businesses, agricultural representatives, and environmental groups, is crucial in developing and implementing effective groundwater policies. Additionally, coordination with state and federal water management policies and regulations should ensure that local efforts are complementary, informed by current datasets, and aligned with broader water resource management goals.

A suggested structure with section headings and content outline follows.

Local participation in groundwater governance

Local engagement is a critical component of governance where decisions impact people. Both Tribes and members of hyperlocal organizations are often the first to see and to feel the impacts of decisions, and neither group is commonly part of the decision-making process. Front-line communities may not be regarded as experts or included in decision-making spaces. In governance practice, shifting the perspective about who holds knowledge and decentering hierarchical credentials can help create a more inclusive process. If governance starts with inclusive, bottom-up practices, there is less need to revise or amend plans later.

Resident concerns

When stakeholder engagement is not prioritized, and an LGU’s planning process is not transparent, the entry of a large water user into an area can create fear and distrust. Groups may form and engage in various ways that are somewhat dependent on the resources of the community members. This can perpetuate environmental injustices for under-resourced and rural communities and increase distrust in government institutions at all levels. For a local government or industry developer, it adds extra time and costs to the development process.

When the course of action is not clear, and governance pathways not established, groups take varying routes to voice their feedback: through the legal system, by seeking media attention, by seeking attention from their elected officials, through a formal environmental review process, or by public protest. Frustration may lead to proactive changes like new people running for local offices or new systems being put in place. However, more commonly it leads to uncompensated effort, unnecessary anxiety, and unhappy residents.

Ideally the connection between a city’s water authority and its role in sustainable regional planning would be understood by the community. There would also be transparency around the state’s role in providing clear direction through laws and regulations, in developing geologic and hydrogeologic knowledge, and delivering it in a timely manner to the city water supplier, economic development team, and Tribes where applicable, so they understand and use the information for sustainable development.

Recommendations

Develop a working relationship with local groups and Tribal organizations that share mutual goals and desired outcomes. Ask for assistance from Tribal partners in reaching out to Tribal communities if no reply or response is received during initial outreach attempts. Provide notice of events far ahead of the event time and plan for multiple modes of communication and outreach based on community preference: different social media platforms, radio, newspaper, flyers, email, phone calls, and in-person visits. Plan for responses to take longer than expected. Expect to reach out to new organizations and committees and work around different cultural calendars.

Do not decide on or develop a plan and ask for Tribal participation as a last step. Tribal officials, Tribal department staff, and Tribal members should be part of the planning process that decides goals, objectives, and implementation of design. Culturally relevant needs should be accounted for and accommodated during the planning process. Ensure the work shows benefit to the community, as decided by the community.

The definition of who is an authority is always a question. Hyperlocal organizations are spaces of informal authority in the realm of groundwater governance. These are spaces occupied by locals, by community members, and by those who are affected. In the case of governance, it is easy to turn to experts – policy, legal, and science experts. It is easy to look to those with credentials, degrees, and other recognized forms of professional authority. It is also easy to ignore that authority and knowledge and expertise can come from experience, and experience may grant no degrees beyond wisdom.

Identify stakeholders through a variety of means – previously contacted participants from previous project phases, regional experts in niche subject matter, social media, newspaper articles, and word of mouth. Hyperlocal, grassroots organizations commonly act as watchdogs by monitoring environmental impacts after large-scale, water-intensive industries arrive in the community.

It is almost impossible to know when an area will become a hot spot of activity, and a grassroots group will shift from being a group of locals to a group with hyper-specific local knowledge and expertise. However, these front-line groups are usually the first to recognize a change in their ecosystems and the first to sound an alarm.

Be willing to educate those who show up in bureaucratic processes and explain technical language. Be willing to listen to and hear the local experience and how the impact is felt despite the intention of the action. Be willing to act in partnership with local knowledge and energy, and to invest in the process.

Where issues have become contentious or entered a litigation phase, it may impact the ability of those in the room to build trust and speak freely. A way to navigate problematic relationships around shared groundwater may be to work with a neutral third party. For example, engineering firms hired to design water-intensive businesses or academics studying a particular water sector might be able to speak generally about site-selection processes, industrial processes, and alternate water sources in a more general way to help a conversation move forward.

As water-intensive industries are driven by financial pressures, there is potential for conflict with grassroots priorities and domestic water users. Information transparency will help to mitigate tensions. With sufficient scientific data to support risk and cost-benefit analyses, land-use and economic development planners will be able to work with utility operators to balance local energy and water supply growth with environmental impacts.

It may be sensible for time reasons to include the staff of an elected official earlier on in the planning process. While the exclusion of elected officials allows government staff the ability to speak freely, early inclusion of political staffers may help to build trust and to ensure there is someone to take part in the practical discussions and hear all the concerns raised in the workshop.

Prioritize building trust at every stage of engagement. To build trust, power differentials among individuals must be recognized and acknowledged. All the actors across the different sectors need to understand how past actions may have contributed to present inequities and commit to a shared future in a shared geology and geographic area.

Note: This information is part of a series of groundwater governance topics Freshwater explored during an 18-month project, which culminated in the report: Towards Collaborative and Equitable Groundwater Governance in EPA Region 5.