The U.S. federal government is one of limited power when it comes to groundwater quantity. While it retains authority to regulate pollution and discharges to groundwater, individual states are responsible for the governance and appropriation of surface water and groundwater within their borders.

Water rights and regulations

States utilize a series of management systems to regulate and permit water allocations. In many cases, a state may use one system for surface water and another system for groundwater. As surface water and groundwater may be connected, and as water ignores geopolitical borders, equitable and sustainable use in regulatory practice requires 1) technical mapping, 2) scientific understanding, and 3) cooperative management agreements across jurisdictions. The states in our region currently work on the first two activities with the third an area for growth.

The eastern United States typically uses riparian rights to regulate surface water, while the western United States either follows the rule of prior appropriation or a hybrid system of both riparian law and prior appropriation. Today, most riparian right states have shifted toward a regulated riparian system which requires a permit for the allocation of surface water used for consumptive purposes, including diversions and withdrawals from waterways.

- Riparian rights are rooted in the English common law system and based on property rights and ownership of shoreland adjacent to a waterway. The expectation is that rights will be exercised reasonably and will not interfere with the riparian rights of others.

- Prior appropriation assumes the first settler landowner to use a water source for beneficial use – including diversion of the water – is granted a priority right.

States that follow riparian water law for surface water regulation also follow the Reasonable Use Rule for groundwater regulation, though both Ohio and Wisconsin practice the Restatement (Second) of Torts Act.

- Reasonable use assumes either the state owns the water, or the water is unowned until in use. Landowners have sole right to groundwater beneath their land, but the water must be put to reasonable use, used on the overlying land, and the user cannot use an unreasonable amount and cannot unreasonably interfere with someone else’s use of their water. Also referred to as the “American Rule.”

- Restatement (second) of Torts Rule is a hybrid of Absolute Ownership Rule and Reasonable Use Rule and uses a combination of factors to determine if water use is appropriate including, but not limited to, purpose of use, suitability of waterway, economic and social value of use, harm caused, practicality of avoiding harm by adjusting method or use of a party, quantity of use, protection of investments.

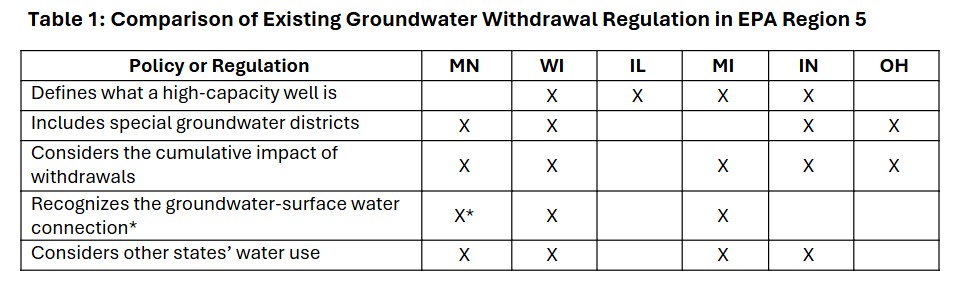

Overall, groundwater governance across EPA Region 5 is fragmented. As such, states' legal frameworks for groundwater governance often do not reflect the current state of hydrologic knowledge. However, certain states have implemented laws, regulations, and policies which address the evolving understanding of groundwater and its sustainable use. The table below compares key aspects of existing groundwater withdrawal regulation in EPA Region 5 (see Table 1 below). State summaries from Phase I of this project include more detail about state agencies and specific management practices.

Groundwater management considerations

Minnesota

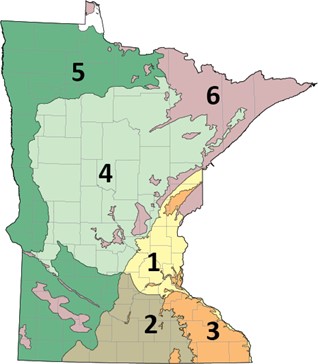

It is within the statutory authority of the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (MN DNR) to permit groundwater allocations based on the availability of water for future generations, the support of ecosystems, the protection of drinking water sources, and to preserve water quality. There is a great difference in groundwater availability across Minnesota, and the MN DNR models its groundwater management approach based on groundwater provinces (Figure 1).

The MN DNR may require monitoring and modeling in places where aquifer knowledge and water is scant. In some scenarios, a 25% decline was determined to be too great. It may take longer to determine the availability of groundwater in some sparsely populated areas because there is less information about the distribution and volume of available water.

Another management approach is a Water Allocation Plan that establishes a maximum yearly volume and leaves the specifics of water sharing up to the high-capacity users in the area. If end users cannot agree, then the MN DNR will get involved. In Groundwater Province 5, that volume is approximately 200 MG/yr. MN DNR can help identify where there may be potential for conflict and if a decline in public water supply occurs, the agency can work with communities and appropriators to limit pumping. However, it takes time to develop such a plan.

In the Twin Cities metropolitan area (Groundwater Province 1), there is more groundwater and hydrogeologic information available. However, there is also greater potential for well interference between high-capacity users and the numerous domestic wells on the urban edge. During periods of drought, when water levels are already low, people tend to increase water usage (e.g. watering the lawn). It was people’s reaction to drought during a time of already low water levels that can create conditions for well interference.

The MN DNR has the responsibility to protect ecosystems that rely on groundwater discharge, including wetlands. Calcareous fens rely on constantly upwelling groundwater to support the calcium-loving plants and have special protections in Minnesota statute, so the MN DNR takes a cautious approach to permit applicants within two to three miles of fens. Water levels in sentinel wells near a fen that show a drawdown of as little as 0.2 feet during a pump test may be determined to be deleterious to a fen. The determination of impact of a well near a calcareous fen may take two to three years.

Wisconsin

The Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey (WGNHS) collaboratively co-manages a groundwater-level monitoring network with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Upper Midwest Water Science Center, which can help identify long-term trends and distinguish pumping from climate impacts to help establish thresholds to avoid harm to ecosystems. Monitoring wells and other field data are used in groundwater flow models to help build better conceptual understanding of groundwater-surface water connections. The modeled impact varies with pumping rate, aquifer properties, the presence of fractures, and general uncertainties about the conditions. Shallow lakes respond differently from deep lakes, and streams tend to experience more impact than lakes.

There are groundwater sustainability challenges in Wisconsin that include the presence of grandfathered-in, high-capacity wells in proximity to groundwater-dependent lakes, the variability of water availability and quality with geology, and quantity issues arising from recent drought conditions. Regulatory challenges have included uncertainty in the decision-making process, and the high number of requests for permits (the WI DNR receives 200 to 300 high-capacity well applications per year).

Opportunities include working at the appropriate scale to manage an aquifer and proactively collaborating with agencies, institutions, and planning commissions at various levels of government; working with agricultural interests on irrigation planning to reduce stress on the system; focusing on cumulative impacts when reviewing water use and approving wells with conditions; making a water quality and groundwater database readily available and developing a well interference process.

Illinois

The Illinois State Water Survey (ISWS) is guided by the 2022 state water plan, a 7-year management strategy that includes surface water, groundwater, and public water supply sources. However, oversight of groundwater withdrawals has not been prioritized despite challenges with water supply in some regions. There is no statutory authority to limit usage of groundwater. The current approach gives more control to local and regional planning groups to manage resource allocation. Ecosystem impacts are not being evaluated evenly.

The ISWS has developed predictive models of deep groundwater systems. The St. Peter aquifer is at risk of further drawdown and dewatering in the northwest suburbs of Chicago. This is driving some suburban communities to request connections to Lake Michigan water. Others seek that water because of PFAS contamination and the cost of treatment.

Local governments want to retain authority over water planning decisions and manage water locally. Planners are optimistic and have a strong belief in technological improvements that solve water scarcity problems or may be reading individual data points and not projecting far into the future. Diverse kinds of engagement are needed early on to navigate questions and tradeoffs because by the time water concerns are evident, hydrogeologists often must deliver difficult news.

Some emerging focus areas in Illinois include water reuse in big infrastructure projects, building pipelines to store carbon in sedimentary rocks, and potable reuse of treated wastewater for irrigation. The state is also working to attract data centers, which can be large water consumers. Winter deicers are increasingly impacting water quality in shallow aquifers.

Collaborative governance in practice

Partnerships which involve state agencies and local organizations generate real understanding about groundwater limitations, especially if the initial focus is on building relationships, deepening the understanding of problems, and incorporating locally based solutions.

Shared successful practices

Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin all share information about existing wells publicly. Education and outreach are used to communicate technical information to the public and explain groundwater models with varying levels of success. Iterative engagement with stakeholders proved successful at generating local buy-in as opposed to technical presentations given by modelers with little to no prior engagement. People trained to communicate and facilitate are good to have on the team.

State agencies have been able to work with federal agencies to leverage technical tools that are not always available locally due to funding or the political climate. Sharing peer-reviewed technical tools for the region through the USGS publications series is a best practice for regional technical information dispersal.

Technical capacity challenges

Management challenges included funding and budgetary constraints, a lack of trained professionals to fill staff openings, and siloed approaches to groundwater management. Even when fully staffed, agencies cannot afford to run a groundwater model for every permit request. Minnesota receives approximately 400 groundwater appropriation permits for review annually, and the groundwater technical team reviews 100 of these requests. Wisconsin and Michigan utilize additive models, with new wells added to an existing model. This allows the technical team to assess the impact on surface water features and surrounding wells.

Despite these models, it can be difficult to assess impact without a lengthy pump test tracked in nearby monitoring wells. Examining the potential for stream depletion from pumping assesses how the water table aquifer responds. This cannot evaluate the sustainability of pumping from deep, confined aquifers. Additional tools or approaches to conduct these assessments are needed.

A water appropriation permit review took 2-to-3 years on average across Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois. Permit review can still take months to years; some permits have been in process for 10 years. Limited resources and technical staff contributed to the long review period, as did the internal structure of agencies. In some cases, the review and approval teams split the work between groups, departments, or agencies, which also adds time. In an example of efficient and streamlined decision making, the Wisconsin process has hydrogeologists in one department who meet weekly to make group decisions.

Consultants have been used to perform technical reviews for permit applications. This can be helpful, but all the work must be reviewed, and when the work must be redone to department standards it does not end up saving time. Reviews may need to include considerations of water quality, from either introduced or geological contaminants, and this can also increase the timeline.

Funding for groundwater technical units is perceived as inadequate, which contributes to staff shortages. Programs are typically funded by permit fees, with a typical high-capacity well-application fee ranging from $125 to $500. This does not support more than a couple hours of a professional’s time. In Wisconsin, a sliding scale for application fees has been adopted within the Great Lakes Basin with a cap of $10,000. Fees are likely to increase as two conservative state courts in Wisconsin recently agreed on the importance of water.

State agencies are increasingly wary of lawsuits, and of issuing a permit which may result in a later lawsuit. Modeling teams are largely sheltered from political considerations, but they may be introduced unwittingly by which permits are elevated for review.

Water-supply challenges

Groundwater supply challenges included declining aquifers, agricultural impacts, and the need to encourage water users to transition away from groundwater as a primary water source and toward surface water.

Declining aquifers and the geologic realities that limited groundwater availability were not always understood by water users, and their aversion to loss plays a role in their behavior. No one wants to give up what they have, and some go so far as to say that if some of the streams must be sacrificed, then so be it. However, some states are seeing people move toward surface water because groundwater permits are too hard to obtain. Ideally people would be encouraged to see groundwater as a backup rather than the main source.

Intensively irrigated areas in central Minnesota, central Wisconsin and along the Illinois River in Illinois are seeing seasonal impacts to surface waters and declining water quality. There is a lack of regulations for agricultural practices yet fear of future regulations. Even if a requirement to not harm a resource through groundwater withdrawal exists, this is not well defined by courts, and every resource is different and must be considered in context of every application.

In areas with groundwater shortages, managed aquifer recharge might help with sustainability. However, recharge and reuse are complicated and have diverse actors influencing decisions and incomplete regulations. It is not a common tool used in the Midwest.

A more holistic One Water approach (surface water and groundwater considered as a connected system) would help. Similarly, unifying land-use planning and water-use planning and aligning them with population projections would lead to a more sustainable future. Different levels of the government may offer contradictory messages; cities complain that “you told us to grow” but now they are hearing “there’s no water here to expand”. This may result from different planning timelines and priorities of various groups. Within infrastructure spaces, most are focused on a 10- to 20-year water plan and the long-term life of infrastructure (100+ years).

Suburban expansion creates the potential for more well interference between high-capacity municipal wells and private wells. It may also result in development in the recharge areas for regional aquifers.

Tools and strategies used to complete groundwater work

Science education and iterative engagement are both a strategy and a tool in ongoing work. Conversations with multiple stakeholders to resolve issues in problem areas are always going to be a challenge. A team will always find a diverse array of skills, including data visualization and science communication, to be helpful. It takes time and energy to convene the right people. Organizers who communicate early and clearly, with a goal toward explaining technical details to stakeholders, are more likely to develop community-oriented solutions and community-approved outcomes.

Existing meetings of state groundwater technical staff across the region could be adapted to include conversations related to groundwater management challenges and successes. However, the big gnarly topics may eventually require immersive, multi-stakeholder, multi-day conversations.

Note: This information is part of a series of groundwater governance topics Freshwater explored during an 18-month project, which culminated in the report: Towards Collaborative and Equitable Groundwater Governance in EPA Region 5.