Treaties have clear implications for the management of surface waters, but the application to groundwater is less clear. Recent rulemaking by the EPA may make it possible to address water as a connected system.

History of treaties

The long history of land stewardship and management began with the original stewards, Indigenous peoples and Tribal nations. The history of the Unites States and Tribal nations has always included treaties. The Supremacy Clause (U.S. Const. art VI, cl. 2), which was ratified in 1788, treaties made “under the authority of the United States remain the supreme Law of the Land.”

“This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.”

– Article VI, Clause 2, United States Constitution

In EPA Region 5, Tribal nations began to sign treaties with the United States in 1785, with the Treaty with the Wyandot, in the state now known as Ohio. This treaty began the practice of annual payments from the United States of goods, supplies, and food in exchange for land concessions from Tribal nations and established boundaries of Tribal land. The Treaty of Greenville was signed 10 years later in the same geographic region with many of the original signatories and recognized that Tribal nations, party to the treaty, retained the right “to hunt within the territories and lands...ceded to the United States, without hindrance or molestation.” This established a practice of usufructuary rights for Tribal nations, or the right to use and benefit from a property while ownership belongs to another.

Throughout 1795 and 1871, the United States and Tribal nations signed multiple treaties, which were ratified by Congress, across the western Great Lakes region. These culminated in agreements like the Treaty of Greenville; a guarantee of goods, supplies, and food from the United States, and expanded to include hiring, covering debts, support of education, and annual cash payments in addition to food and other goods in exchange for land concessions from Tribal nations. These treaties also established Tribal land boundaries. Treaties with the Ojibwe nations in what are now Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota included usufructuary rights including the retained rights to make maple sugar, hunt and fish, gathering of wild rice, including in ceded territory, and occupy the land.

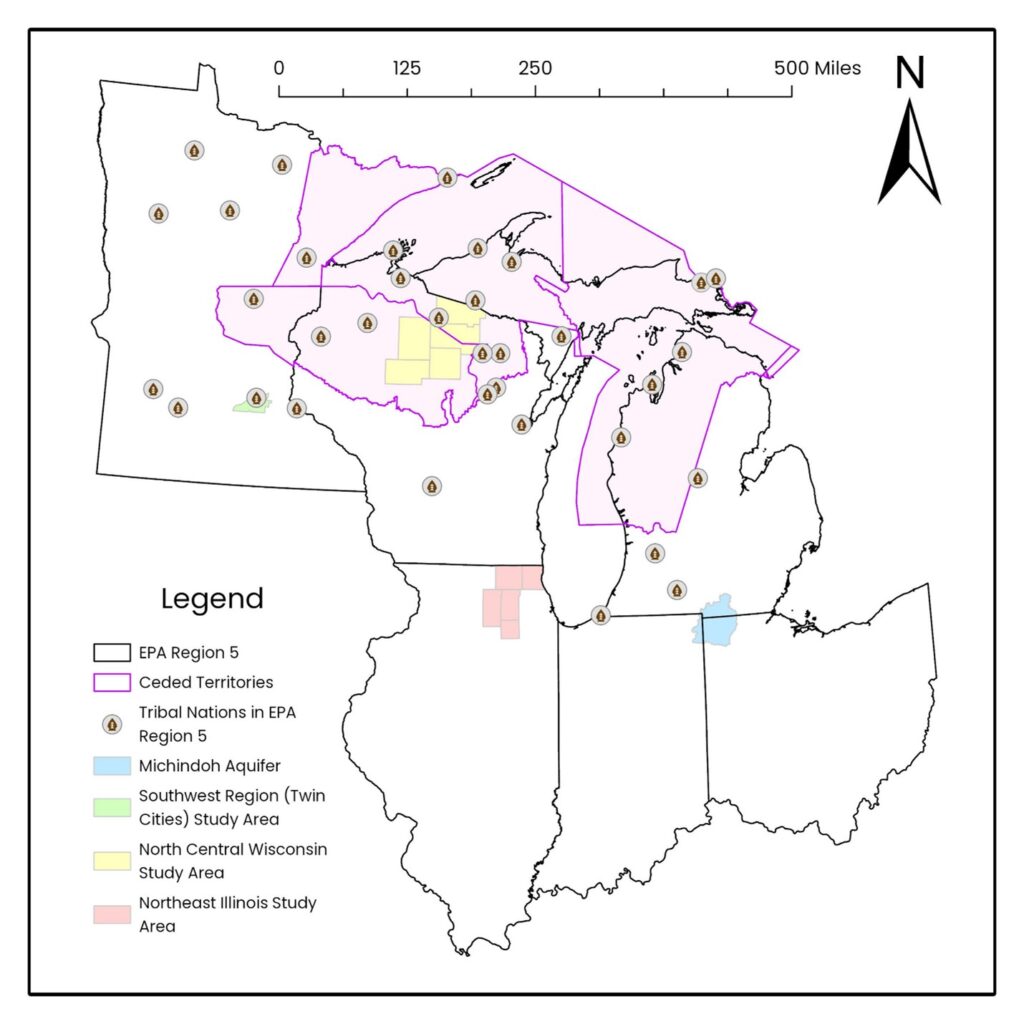

These treaties established boundaries for Tribal lands known as reservations and, in the case of some Ojibwe nations with usufructuary rights, established land known as “ceded treaty territory” in which those rights could be asserted. Certain Tribes have co-management agreements with the federal government in ceded territories. Co-management is supported through intertribal commissions including Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), Chippewa Ottawa Resource Authority (CORA), and 1854 Treaty Authority which have the authority to regulate and enforce within their mandates.

The sustainability of groundwater is crucial for upholding treaty-reserved usufructuary rights. Beyond 1871, court cases at the state and federal level both upheld and challenged the rights of treaty holders. In 1905, a U.S. Supreme Court Case concluded that Tribal nations retained any rights not expressly surrendered in the treaty, including the rights to fish, hunt, and other privileges. In 1908, Tribal water rights were acknowledged, particularly related to the survival and self-sufficiency of Indigenous peoples. In 1983, the Winters Doctrine was extended by holding that water rights are reserved sufficient to support hunting and finishing rights as part of the purpose of the treaty.

Treaty-reserved rights

A rule on water quality standards (WQS) designed to protect treaty-reserved rights (TRR Rule) was explored with the EPA to determine if it could be used to protect groundwater, especially where strongly connected to surface water and where treaty territories cross state boundaries:

Groundwater-fed streams and springs have cooler, more stable temperatures and differing water chemistry from surface water. Cold-water fish and the organisms they depend on are potentially at risk if groundwater is depleted. Could the TRR Rule be used if enough groundwater was extracted to warm groundwater-fed streams?

Healthy wild rice beds have been linked to areas of groundwater upwelling. Could the TRR Rule be deployed if groundwater withdrawal impacted wild rice viability?

In a reverse scenario – where shallow aquifers have been breached by pipeline emplacement-cold upwelling groundwater into tannic (acidic) surface-water bodies has the potential to change pH and temperature creating unfavorable habitat for bog plants and life. Could the TRR Rule be used to protect those waters from harmful groundwater discharge?

The process for implementation of the TRR Rule as outlined by the EPA is portrayed below.

Treaty-reserved rights applied to groundwater

The TRR Rule was designed to apply to surface water, not groundwater and to clarify EPA’s role in assisting Tribes with surface water quality standards. A surface-water standard can be quantity-, quality-, temperature-, or contaminant-based. However, surface water can be protected for the use of recharging groundwater as a drinking-water source or in support of a treaty-reserved right. EPA staff acknowledge that surface water and groundwater connections have not been explored thoroughly in Region 5 compared to other water-scarce parts of the country. The TRR Rule would allow Tribes to assert rights for consideration to EPA related to surface water interaction with groundwater.

Implementation of the TRR Rule could require designating the use of a surface water feature by using a criterion that would ensure protection if interaction with groundwater occurs. An assertion could also focus on a use impacted by surface water impairments that require groundwater recharge. For example, there are designated uses for surface water that involve treaty-reserved rights to gather manoomin (wild rice) or fish. Changes in groundwater quantity can impact aspects of surface water chemistry like dissolved oxygen, salinity, or temperature. To the extent that waters under review with the TRR Rule are supported by adequate groundwater, they could be subject to an updated standard. The volume of cold water needed to maintain an existing thermal standard is dependent on the air temperature as well as groundwater temperature and volume. Citing a thermal standard could require documentation of any change in temperature to a cold-water stream that was a result of climate versus groundwater volume or temperature change.

Tribal rights for interstate ceded territories

States receive delegated authority from the EPA to administer environmental programs, like the WQS program, which sets standards within the state borders. Tribes who have applied for and been approved for Treatment as a State (TAS) also have that same delegated authority, similar to a state, to manage and implement federal environmental programs for their Tribe within Indian Country. A Tribe must apply for and be approved for TAS status for each environmental program separately. States have assumed delegated authority and have the individual authority to set WQS and submit revisions to the EPA.

The general practice in Region 5 has been to extend consultation to all of those in the treaty area. For example, consultation in the 1837 Treaty Territory would include Wisconsin and Minnesota Tribes. There has not been formal interstate coordination in Region 5, but members of state agencies discuss border-spanning issues frequently. Parties can request EPA engagement to negotiate a solution across states and Tribes if needed, but ultimately the authority lies in the state’s process.

The TRR Rule has already faced legal challenges. As of summer 2024, a group of twelve western states has alleged the TRR Rule exceeds EPA’s Clean Water Act authority. The initial lawsuit was answered with a motion to intervene served by 12 Tribes, including seven Tribes from Region 5 and accompanied by comments from Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife. Despite the EPA’s assurances otherwise, the TRR Rule may further be challenged for effectively limiting existing water rights. The geographic extent of Tribal reserved water rights for fishing may have significant effects on water quality standards and the granting or denial of pollutant discharge permits throughout the United States; particularly in states where multiple federally recognized Tribes hold reserved rights to aquatic or aquatic-dependent resources.

Note: This information is part of a series of groundwater governance topics Freshwater explored during an 18-month project, which culminated in the report: Towards Collaborative and Equitable Groundwater Governance in EPA Region 5.

Impressive information. Thank you.

God afternoon,

Looking at the map, it is not inclusive of the all the ceded territory in Minnesota that the Treaty Reserved right rulemaking applies to. There is a large section missing for the 1855 Treaty territory in Minnesota. I would be willing to share a shapefile with you, if it would help to update your map.

Sincerely,

Renee Keezer

Water Resources Manager

White Earth Natural Resources

(218)935-3651

Hi Renee, thanks for letting us know, and sorry for the slow response here. We’ve passed this on to our groundwater team!