Freshwater’s good friend and collaborator at the St. Croix Watershed Research Station, Shawn Schottler, who holds a doctorate in environmental engineering, reduced his research hours to run his family’s multigenerational Christmas tree farm in Wisconsin—at the beginning of the worst drought they’ve ever seen. The dryness exceeds even the intensity of the Dust Bowl, which the family well remembers. They’ve had about three inches of rain to date. For comparison, that’s at the low end of annual rainfall for the Sonoran and Mojave deserts—plus they’re getting the temperatures to match. At the end of June, all new growth was dead on the branch.

Freshwater’s good friend and collaborator at the St. Croix Watershed Research Station, Shawn Schottler, who holds a doctorate in environmental engineering, reduced his research hours to run his family’s multigenerational Christmas tree farm in Wisconsin—at the beginning of the worst drought they’ve ever seen. The dryness exceeds even the intensity of the Dust Bowl, which the family well remembers. They’ve had about three inches of rain to date. For comparison, that’s at the low end of annual rainfall for the Sonoran and Mojave deserts—plus they’re getting the temperatures to match. At the end of June, all new growth was dead on the branch.

Instead of helping us with dating sediment and devising new schemes to protect surface water while providing habitat, Shawn wakes up every four hours to move the irrigators and run them for an hour in an effort to save the trees. By Aug. 1, the remaining trees will either be dead or dormant so he can give up on watering and start to sleep again, if he can.

Weather whiplash is how a member of Lower Sioux community put it. Their tiny environmental resources team had recently been trying to adapt to the challenges posed by the wettest few years on record in western Minnesota, and now they are looking at the lowest levels in the Minnesota River in memory.

This is very much what the long-term climate projections showed: more intense rainfall separated by longer periods of drought.

Much of what we are experiencing in the upper Midwest can be traced back to warming of the Artic. Jennifer Francis, who holds a doctorate in atmospheric sciences, explained the connections to a Freshwater audience in a past Moos lecture. In the early spring of 2018 we were reeling from outbreaks of the Polar vortex. She appeared on Paul Huttner’s Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) show at the time, and he interviewed her again last week for help putting the new weather extremes into perspective. National Public Radio also consulted her on July 29.

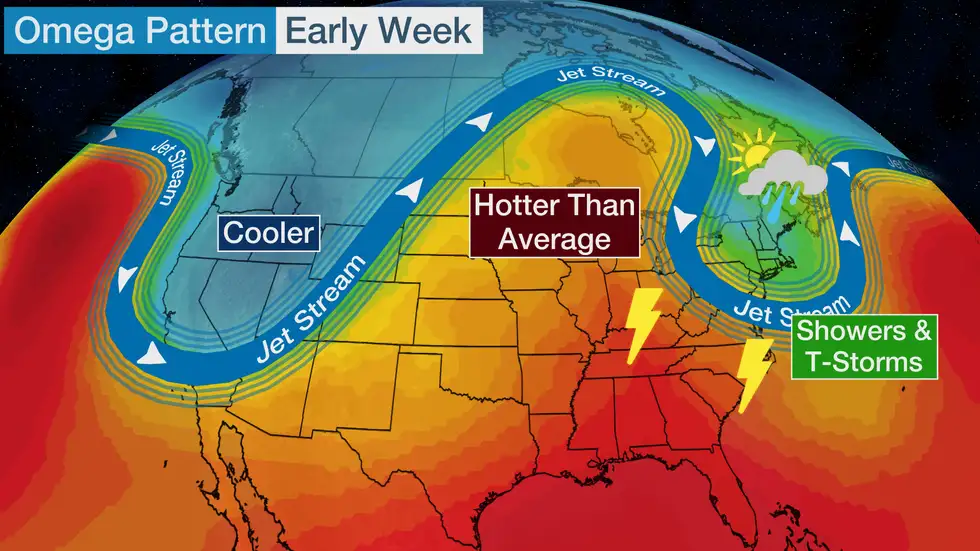

Arctic warming plays a role in how the high and low pressure systems set up and how long they persist. This in turn affects the sinuosity of the jet stream and how quickly it moves across the continent. A sinuous jet stream means that at times we are dominated by air that originates much to the north of us. It also means that very hot air that originates to the south can extend farther north than ever before, and even spin off into a separate gyre (Portland heat dome event)—called the Omega block for the shape it takes: Ω.

This is happening around the globe. During their conversation on MPR, Jennifer told Paul the same underlying patterns that are behind the heat wave in the Pacific Northwest and Minnesota are also the cause of the devastating floods in Germany and China. We have created extreme weather swings while at the same time stalling the jet stream that keeps heat waves, cold snaps and rain over an area for longer, intensifying their impact.

So far, no one is talking (seriously) about geo-engineering the jet stream, although other atmospheric manipulations are cautiously being investigated.

If we can’t control these weather patterns, then the task at hand is to build water resilience into our systems and ecosystems. That is why Freshwater is focused on improving our ability to adapt to water extremes for all communities, especially those most vulnerable that may lack the capacity to adapt. A partial list of recent Freshwater projects shows how we are addressing surface water and groundwater resilience both at home and across the Great Lakes region.

Our work may not always make the news cycle, but we are playing the long game. We’re building relationships so we can help elevate community-led solutions representing diverse perspectives, we’re recommending policy based on science, and we’re advocating for best practices from the various governance structures across the Great Lakes states and tribal governments—all so we can adapt together to face an uncertain water future.

- Banking groundwater—removing policy barriers and finding a permitting path to allow cities to safely store water underground for long-term drought security

- Water storage program—establishing a program to store water in agricultural landscapes to smooth out the highs and lows in streamflow.

- Groundwater Governance in the Great Lakes States—building relationships across five states and tribal nations within that geography to elevate best practices for sustainable groundwater management for the region.

- Hennepin County Bedrock Collapse Inventory (pdf)—identifying where water infrastructure and vulnerable bedrock units have caused rain and leak-driven sinkholes in the past

- Hennepin County Landslide Inventory—identifying where precipitation-driven landslides create risk to people and infrastructure

- Water reuse—promoting best practices for reusing rather than discarding ancient groundwater

- Irrigation efficiency (pdf)—identifying barriers to adopting irrigation scheduling and other water-saving practices