There’s a film premiering on Feb. 19 that Freshwater just couldn’t ignore. The setting? Lake Superior. The title? “Freshwater.”

So what is this film all about? The feature-length version premiering in February expands on a 23-minute film focused on the surfing community of Lake Superior. Filmmakers wanted to learn about how the lake’s winds work, according to a Duluth News-Tribune story—but once they started talking to scientists at the Large Lakes Observatory, they learned a lot more than that.

Large Lakes Observatory

The Large Lakes Observatory is a research institute at the University of Minnesota-Duluth. Founded in 1994, the observatory includes researchers studying the world’s major lakes through a variety of disciplines, from biology to chemistry to physics—and more.

To learn more about the science included in the longer “Freshwater” film, I talked to Elizabeth Minor, a UMD professor with a doctorate in marine chemistry and geochemistry. Minor joined the Large Lakes Observatory in 2005, when she and her husband, a professor of physics and astronomy, moved to Duluth to fill positions at the observatory, which was serendipitously hiring both a physical and chemical limnologist. Before this move, Minor’s work was in chemistry in Norfolk, Virginia.

Minor explained that because of the size of Lake Superior and the other large lakes they study, researchers must use oceanographic approaches. “You can’t go out in a canoe and understand what’s going on all across Lake Superior,” she says. The data collection and approach to research questions just isn’t the same as the way researchers study small lakes.

The observatory encompasses a variety of disciplines, but Minor’s own research is about carbon cycling in aquatic systems. She looks at the organic material that gets eaten in lake systems, the inorganic carbon released by respiration and fixed with photosynthesis, and how that inorganic carbon acts as a buffer stabilizing pH against inputs of acids (such as acid rain or acidic mine waste).

A startling discovery

Minor’s work takes her to large lakes around the world. Sampling Lake Malawi in eastern Africa in 2011, Minor came across something she wasn’t anticipating—plastic. Fibers from what looked like shopping bags and blue tarps were showing up in samples taken from a 300 meter depth. “I would have expected it in surface waters, since plastics usually float,” Minor says. Besides that, Malawi is a pretty remote lake.

Plastics were the dominant particulate matter in her samples from Lake Malawi. When Minor thought about it, it made sense: The strong sunlight and faster cycling of particles from algae to fish bodies means the only particulate matter not reworked quickly is plastic.

What happens next?

Researchers have found plastic microfibers in water, in sediment, and in fish stomachs. But are the plastics getting beyond this point?

The current tools used to look at nanoplastics only work for particles measuring 20 microns or larger. However, particles that size don’t cross the gut barrier—to do that, they have to be smaller than 5 microns. This means that previous studies of larger particles haven’t shown whether microplastics pose a physiological problem to animals or people. Minor aims to measure the amount of smaller plastic particles in the environment so that toxicologists can use the data in their studies.

Instead of following previous methods, Minor relies on another technique: flow cytometry. This method, usually used in medical research, uses a laser beam to detect and measure characteristics of a population of particles—and it can measure particles down to .2–.5 microns.

Simply put, the science of collecting and analyzing environmental microplastics is still developing. “We’re still looking at what’s out there, how much, what sizes, and what polymers,” Minor says.

Where do microplastics come from?

These particles enter the environment through direct litter that breaks down, wastewater treatment plants and septic systems, and atmospherically—blown out of dryer vents.

Microplastics in our big lake

In Lake Superior, Minor’s lab group, working with colleagues from the Schreiner, Maurer-Jones, and Hrabik groups (also at UMD) have found microplastics in water throughout the water column, in sediment, and in fish. These are all very low concentrations, though, relative to other particles present. The amount of plastic found in fish is small, and it’s not present in all the fish they catch. The concentrations in surface waters are roughly equivalent to amounts found in the North Atlantic.

More and more students are interested in this problem, though, and the lab is growing. One course where students might study this problem, along with other topics surrounding Lake Superior’s water, is Limnology Practice One.

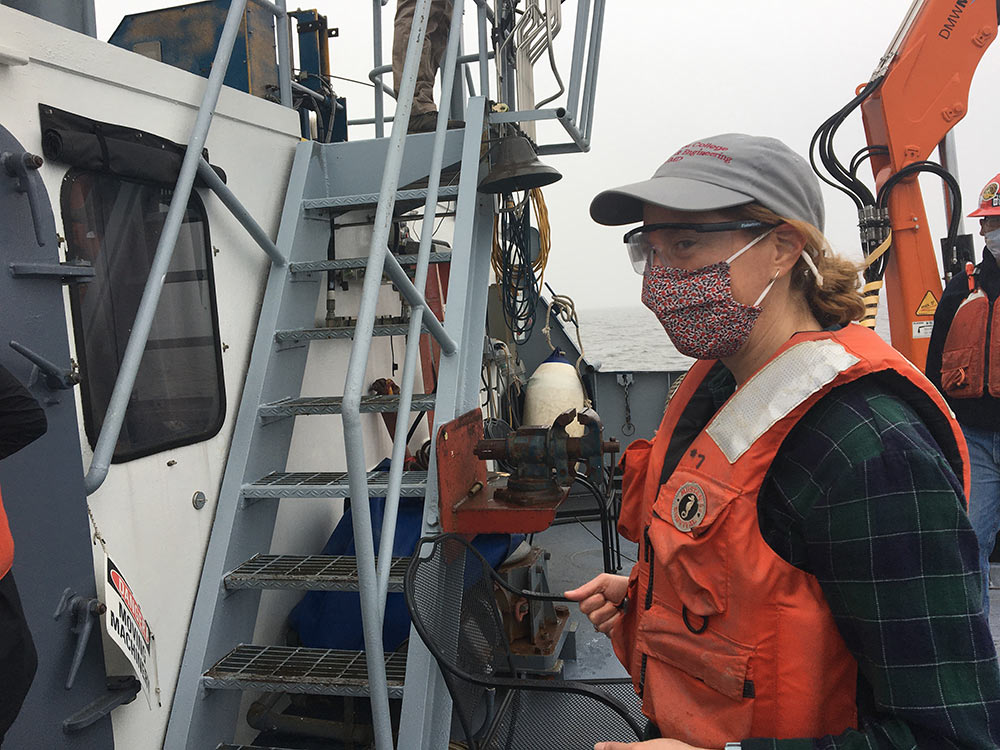

In this class, graduate students spend two days on a research boat called the Blue Heron, collecting samples to process according to their own work plans. Last year, when seven students took this research trip along with Minor and other observatory scientists, a film crew accompanied them.

The crew was shooting for the feature-length version of “Freshwater.”

Filming ‘Freshwater’

Lake Superior contains 10% of the world’s fresh water, and filmmakers wanted to learn more about the science of the water. They had told the story of the surfing community, and of personal connections to the lake. But research was also an important part of the story, so they reached out to Bob Sterner, the observatory’s director.

Besides the trip on the Blue Heron, filmmakers talked to the researchers and filmed inside their labs. When the film premieres, viewers will see how filmmakers expanded the narrative from the personal lake connection to a broader perspective.

I asked Minor what she hopes the film teaches people about her work—and about fresh water in general.

“This is an amazing resource,” she says, “but it’s not infinite: We have a stewardship responsibility to keep it in good shape.”

On top of that, she had another message. We’re affecting the lake, but the lake is also powerful. “If it’s one person versus nature, nature will win,” she says. “Don’t go out in bad weather, and pay attention to what the lake is telling you.”

Learn more

Large Lakes Observatory

“We’re trying to really understand how the lake works on a basic level, how it’s changing, and what we can do to keep it the most functional and beautiful place that we can,” Minor says.

That goal is perfectly in line with our mission at Freshwater, so we invite you to learn more about the work happening at the observatory—and to attend the premiere of the film. Minor will be on the Q&A panel after the screening.

Attend the premiere

Full-length premiere: Feb. 19, 2022 at the NorShor Theater in Duluth, Minnesota. Buy tickets and learn more, and see the 23-minute version (scroll to the bottom to watch this short version).