The Great Lakes region is perceived as being water-rich, and states promote this asset to attract water-intensive industries. While it is true that the region hosts usable groundwater, the supply is not limitless or evenly distributed, and in places it will be depleted within decades.

Groundwater use is clearly not sustainable in areas where there are now large cones of depression or where streams, wetlands and lakes are seasonally impacted. The adequacy of groundwater to sustain existing and new users requires evaluation on a case-by-case basis using an appropriate level of detail to describe local hydrogeologic conditions; a comprehensive summary of current use; a groundwater monitoring network; and future-scenario modeling that includes climate impacts. It requires a system of governance.

- Groundwater governance encompasses how people and their institutions collaborate across various jurisdictional levels to establish laws, policies, and decisions to manage the groundwater they share.

- Groundwater management encompasses the practical implementation of those laws, policies, and decisions.

Although in its early stages, a groundwater governance system has progressed in EPA Region 5 as evidenced by the increased sharing of information and strategies against the latest groundwater pressures. State, Tribal, and municipal staff, residents, and the media in targeted areas are paying more attention to how decisions about groundwater are being made. As recent threats to community water supplies coincide with weakening federal oversight, state legislators are trying to identify and fill these policy gaps, while respecting the ability of local governments and Tribes to determine their own futures.

Although there are many differences across the region, there are shared values that prioritize the use of groundwater for human consumption and support for ecosystems. The challenge now is how to support regional economic development and the water needs of large-volume water industries, whether that is agriculture or a newer high-tech enterprise.

Regional groundwater governance systems

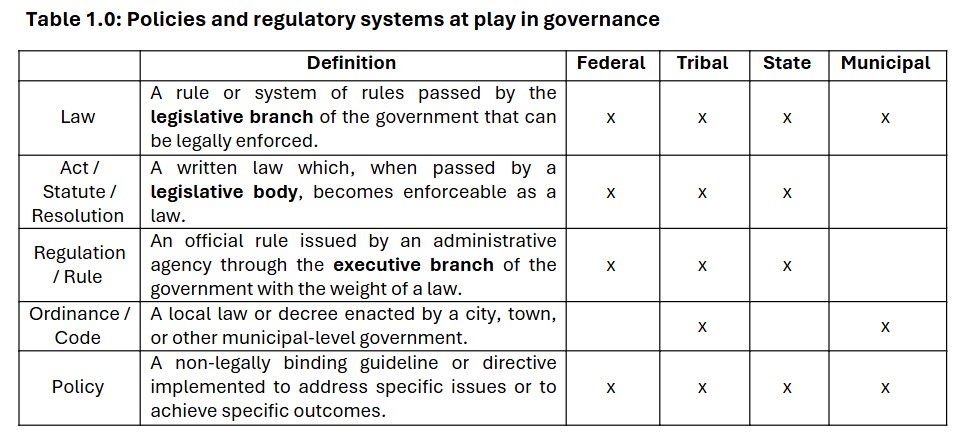

The multi-jurisdictional groundwater governance landscape present across the region today is complex and at the same time, not comprehensive or well connected. Groundwater is managed by a combination of appropriation doctrines, pollution regulations, and land ownership rights that are set by the state. At times, a dissonance exists between the intention and effect of these systems which encompass laws, acts and statues, ordinances, regulations, and policies (see Table 1.0).

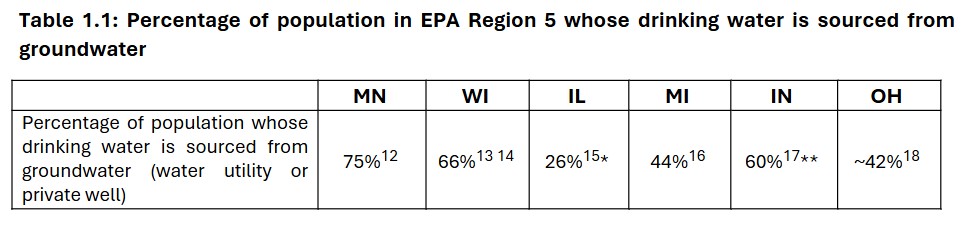

In the United States, approximately 38 percent of Americans use groundwater as the primary source of drinking water, though the numbers are higher in EPA Region 5 (Table 1.1). While surface water and groundwater are often connected, they are regulated differently, and water quality is regulated differently than water quantity. Frequently, regional planning agencies or planning commissions share responsibilities and coordinate across municipalities.

*In Illinois, ~65% of community water systems are also groundwater dependent.

**Currently there is only regional data for drinking water sourced from groundwater in Indiana.

Regional planning to support governance

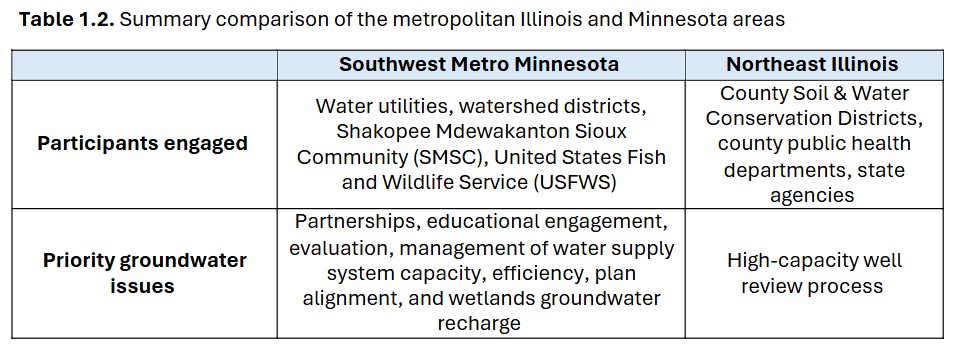

Metropolitan areas in EPA Region 5 are facing complex, multi-jurisdictional groundwater challenges. New climate and development forecasts reveal the long-term consequences of unchecked growth. The densely populated, urban fringes of Chicago and Minneapolis-Saint Paul face specific regional development pressures – including competition for the domestic water supply while still sustaining and increasing economic growth and development. These two metropolitan areas have differing priority issues and local and regional governance strategies.

Regional planning agencies

In Illinois and Minnesota, two regional planning agencies are the state-recognized authorities, which oversee two seven-county regions for the major metropolitan areas – Chicago and Minneapolis-Saint Paul. Both agencies are responsible for producing comprehensive water supply plans and forecasts for the future. Within these regions, case studies from northeast Illinois and southwest metro Minnesota are highlighted to compare priority issues, and strategies which are currently utilized to address governance gaps and barriers. In northeast Illinois, the Water Use Act of 1983 and the high-capacity well review process were assessed. In southwest metro Minnesota, the water supply planning process was assessed as part of the overall water policy plan.

In 2018, the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) produced its comprehensive 30-year regional plan, and the updated plan was adopted in October 2022. The comprehensive regional report, ONTO 2050, noted that northeast Illinois highlights three water areas of attention for the region: 1) water use versus water demand; 2) conservation and efficiency efforts; and 3) existing groundwater supply. This comprehensive road map also incorporated regional water demand forecasts, sustainable supply values, and water supply sustainability plans. ONTO 2050 was developed by CMAP in consultation with other planning agencies, research institutes, and municipal bodies to identify anticipated areas with water supply challenges and worked with regional partners to propose potential solutions to barriers.

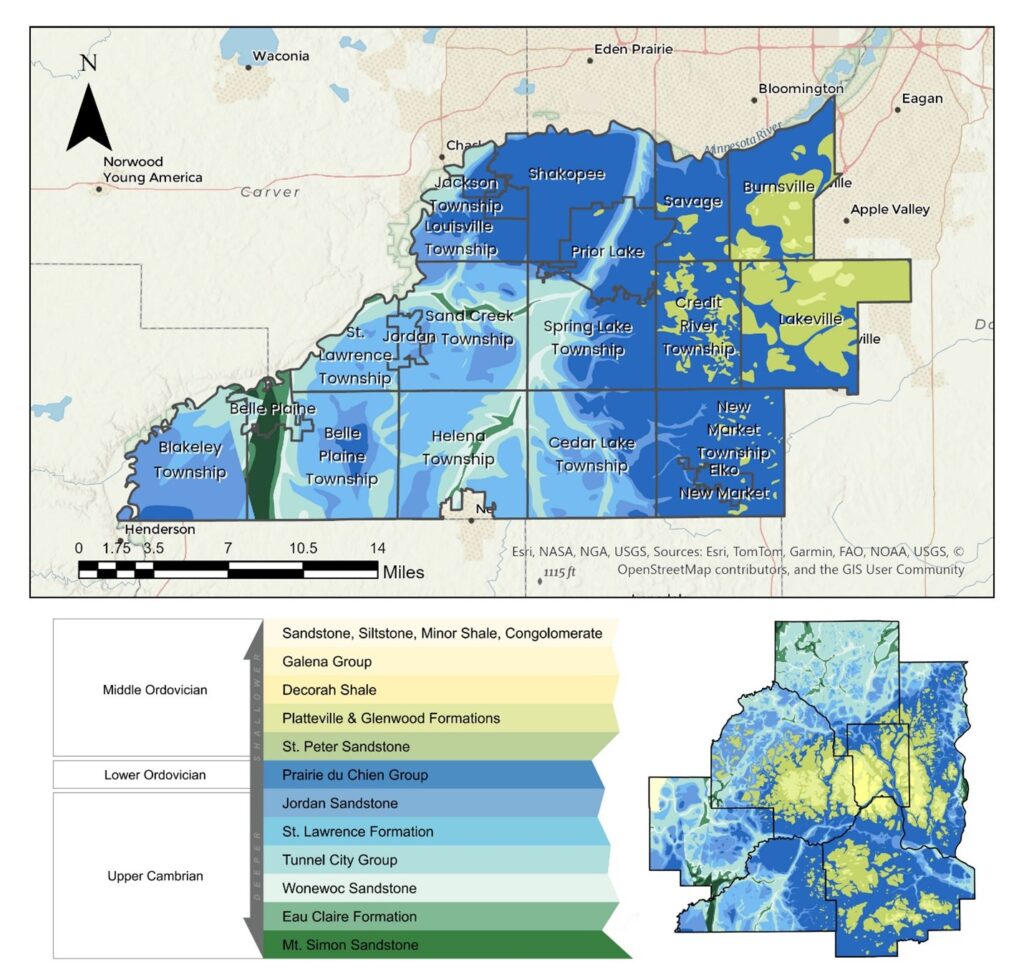

The Metropolitan Council (Met Council) water planning team was created in 2005, with the publication of the first regional Water Policy Plan in 2015. A comprehensive regional report, Imagine 2050, was released in 2025 with the updated Water Policy Plan, and included water demand projections, groundwater model projections, and groundwater optimization modeling. To better align regional planning with local and subregional water supply needs, the Met Council engaged water professionals who impact and are impacted by water supply. In the Water Policy Plan planning process, five subregions were tasked with identifying the activities and barriers necessary to address current and anticipated water supply challenges over the next 25 years. The southwest metro subregion was the only subregion in the water supply planning area with a Tribal nation, the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community (SMSC). SMSC is a well-resourced Tribal government with a long history of collaborating with local governments on water supply planning.

Geology overview

Northeastern Illinois

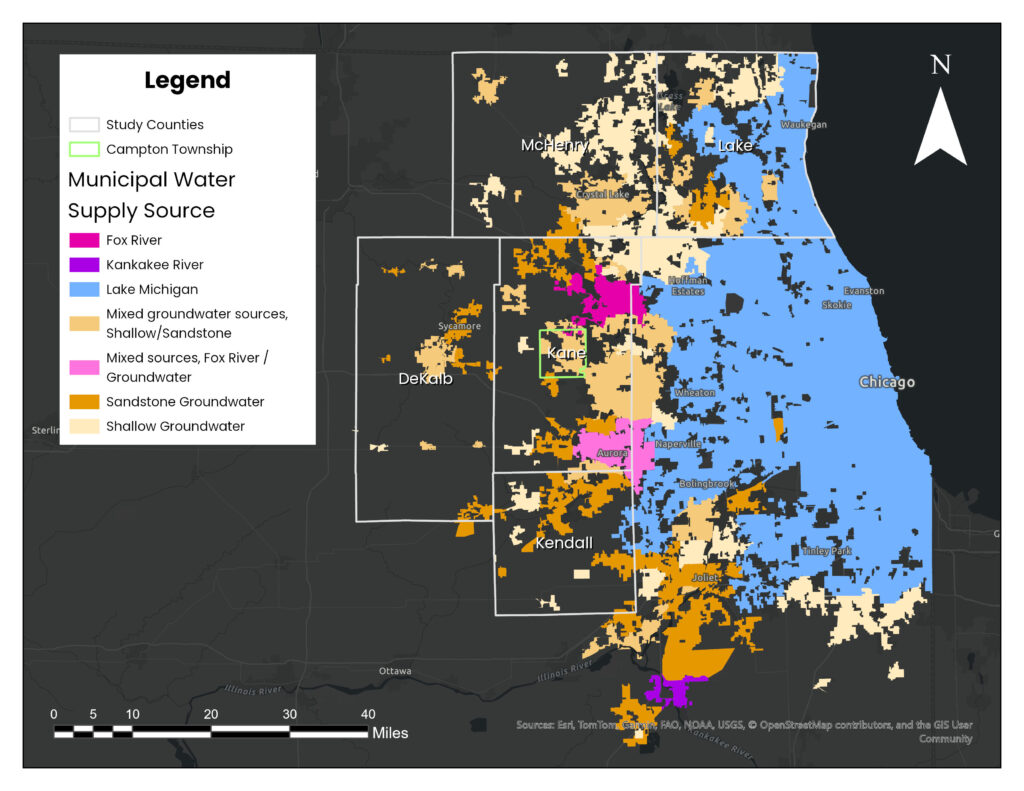

By international agreement, only municipalities located within a Great Lake’s watershed are approved to use it for drinking water. Illinois is an exception dating back to the 1800s when the Chicago River was reversed to protect lake water quality. Chicago gained access to billions of gallons of Lake Michigan water at this time to dilute the pollution diverted from the Lake. This decree has been challenged over the years (e.g. Wisconsin in the 1920s over lake-level lowering; Michigan in 2010 over the introduction of invasive species) and the Court retains jurisdiction. The 1967 Supreme Court ruling allows Chicago to use 2.1 billion gallons of lake water per day. Recently, the city of Chicago agreed to sell roughly 0.05% of its diversion allocation to Joliet, a suburb 35 miles to the southwest.

A significant cone of depression exists in northeastern Illinois due to heavy pumping in deep wells and withdrawal rates which exceed recharge rates. Northeastern Illinois diverts water from Lake Michigan for domestic water supply and distributes some of the supply to nearby suburbs that lie outside the watershed of Lake Michigan. Suburban communities that do not currently receive Lake Michigan water must rely on groundwater and other surface water sources like the Kankakee and Fox rivers.

Southwest metro Minnesota

The southwest metro region of Minnesota has a bedrock aquifer shared across the region. There are significant cones of depression projected based on current use. The Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul primarily use surface water for drinking water, but as suburbs extend away from river and lake sources, private domestic wells and public municipal water suppliers increasingly rely on groundwater.

Water management and water use

Northeast Illinois

Currently, water use is expected to exceed available supply in some areas, but overall water use is expected to decline due to conservation and efficiency measures which are trending to outpace both population and employment growth. The existing water supply is mapped to show where demand may exceed availability at the county level and how much water can be pumped without causing further desaturation of deep aquifers or harm to groundwater-dependent ecosystems.

Southwest Metro Minnesota

Met Council oversees water supply planning for the region but shares responsibility for water management and water use with local public utility providers, who provide drinking water, manage surface and stormwater, and treat wastewater. At present, the water supply plan highlights the benefit of increased collaboration, supports sustainable approaches to water use, and encourages water conservation practices and programs.

Priority issues

Previous work CMAP and Met Council during comprehensive regional planning highlighted priority issues for stakeholders, including specific gaps and barriers in existing policies and topic areas. As CMAP’s comprehensive planning process took place in 2018, priority issue areas were clear, and the agency was able to focus on a specific policy and review the process for high-capacity well permits. As Met Council was in the middle of its comprehensive planning process, priority issues emerged during water supply area planning meetings. These meetings also brought forth gaps in governance systems and governance barriers faced by residents, city planners, and other government staff.

Northeast Illinois: high-capacity well review

As a result of this work and previous work during Phase I of this project, CMAP developed a report on the implementation of the Illinois Water Use Act of 1983.2 The report focused on the current notification and review process for high-capacity wells, and sought to answer how effective the Water Use Act of 1983 is at generating a cohesive and systematic process for sustainably managing high-capacity wells.

According to CMAP’s report, Securing Illinois’ groundwater future, the Water Use Act of 1983 was a reaction to historic population increases and development patterns that were causing conflicts among communities with interconnected groundwater systems. These conflicts motivated the Illinois Farm Bureau and farmers to lobby the Illinois legislature which successfully passed this act. The Water Use Act of 1983 replaced the absolute ownership doctrine with a reasonable use doctrine. The Water Use Act of 1983 also established a way to restrict groundwater withdrawals during emergencies in limited areas of the state, and a way to provide public notice and review of new withdrawals that are both planned and deemed substantial (i.e., greater 100,000 gallons of water per day).

In 2010, the Water Use Act of 1983 was amended to require water-use reporting among commercial, industrial, and irrigation high-capacity well users. Prior to publication, the effectiveness of generating water-use data for users had not been well explored. The report identified many misalignments in water-use reporting and indicated that the policy may not be effectively administered and may contribute to data gaps in the future.

Securing Illinois’ groundwater future also identified barriers for permit requesters and agency staff including duplicative notices for water quality and high-capacity well reviews, lack of guidance provided to define the scope of the review needed, and no dedicated revenue stream for the high-capacity well review process. The duplicative notices also required more staff time than was available at current staffing levels.

Southwest Metro Minnesota: water supply area planning

As one of the subregional planning areas, stakeholders met at two different workshops to discuss and brainstorm local issues. From these workshops five primary focus areas were identified in the Southwest Metro water supply planning process: partnerships, education and engagement, evaluating and managing water supply system capacity, efficiency, and plan alignment.

Partnerships

Water governance is fragmented. Collaboration is needed to reduce siloed decision-making, to address regulatory barriers to new approaches, and to support communities’ abilities to enact local controls that support sustainable water supplies. There is no single entity that oversees groundwater sustainability in the southwest metro area of the Twin Cities. There are multiple state agencies, federal agencies, a Tribal nation, and community members who participate in the process.

Cross-jurisdictional partnerships typically take more time to develop. Political motives which drive action may also reduce the political desire to work together, and any miscommunication may hinder future endeavors. Partners may also have different supply needs, and lead to a lack of interest in regionalization efforts and this motivated self-interest contributes to siloed decision making. Local governments frequently lack the capacity to support community engagement efforts, which limits community voices in the decision-making process as well.

Education and engagement

Ongoing resources are needed for education and engagement at the state, regional, and local levels for efforts. Current approaches to outreach and education are not hands-on and lacks trained facilitators. Funding and staffing are necessary for efforts like water efficiency and transmitting local information back to the community. The Met Council subregional groups are a success story. Water supply leaders are valued for attending and sharing their feedback. These leaders felt heard and were able to coordinate on a regional level.

Community outreach approaches also do not rely on existing connections between members of the community, which contributes to lack of participation from private well-owners, Indigenous community members, and others rural residents. Engagement efforts tend to focus on those with credentials, technical, or academic backgrounds, or those who are felt to inform decision making, rather than those impacted by decisions.

Evaluating and managing water supply capacity

There is a need to better understand the demand for economic development in the area. Existing high-volume water users and commercial water users – both of whom have been in the southwest metro of Minnesota for a long time – and prospective and incoming high-volume water users offer economic opportunities for smaller, more rural towns outside of the metropolitan bubble. However, uncertainty and gaps in information about factors like changes in climate, geology in buried bedrock valleys, and emerging anthropogenic and geologic contaminants make evaluation and management of groundwater supply challenging.

At present, water supply models are not equipped to address emerging water supply challenges or support current or emerging industry requests from high-volume water users. There are also gaps in the existing monitoring networks that would require additional funding to expand and additional staff capacity to maintain. Current regulations also do not support, and in some cases actively restrict or prevent, water reuse and recharge opportunities. Weather changes have also impacted managers’ ability to effectively evaluate and manage the water supply and water capacity. Multi-year droughts or flooding events strain water supplies and distribution systems and disrupt the water supply projections and models.

Land use planning also contributes to water supply management. New housing developments drive domestic water use in an area, and industries like agriculture, manufacturing, and technology all consume more water than high-volume water users. Industrial users are also more likely to produce potential water contaminants like nitrates from fertilizer run-off and PFAS from manufacturing processes. Contamination and development also threaten natural places like fens and springs. Water utility rates may not cover system operation and maintenance costs, and any contamination would require additional specialized equipment for treatment. Additional economic development revenue to supplement

Efficiency

While there are programs in place to incentivize efficient use of water resources, there is a knowledge gap among water users about how to access those programs. As weather patterns change, there is a question as to when or if water conservation and efficiency programs should be implemented, and many communities are still behind on implementing efficiency programs. Water efficiency programs also result in less revenue for water utilities, which can create a funding challenge for public utilities. However, most water efficiency programs also rely on community engagement to drive participation and change existing water use behaviors. Currently, there is a lack of both staff capacity and sufficient training to support this level of community engagement for robust water efficiency programming.

Plan alignment

During the final workshop convening, the Met Council inquired about what role the regional governing body should play for the different entities navigating these challenges and how they could support them moving forward. Alignment of regional planning efforts with local planning efforts may increase engagement with and implementation of these plans. Financial resources may be more limited at the local level, and through aligned planning, those resources may stretch further when combined with regional planning efforts. However, funding for both jurisdictions is dependent on the legislature or regulations or both. This does inhibit the ability or interest of participants to engage in alignment or in implementation.

Best practices

Northeast Illinois: high-capacity well review

While developing Securing Illinois’ Groundwater Future, CMAP found key ways to improve the high-capacity well permitting process and the overall water-use reporting process: 1) Groundwater management objectives should include quantity measurements; 2) resources and systems that already exist could be better coordinated. Available information exists about current water users, but that information could be shared across agencies to reduce redundancies and reapplications. Improved administrative funding to coordinate would reduce the need for administrative time spent processing permit applications with the same information. This would also allow the well-review process to connect to decision making goals and align review criteria with groundwater management goals.

Southwest Metro Minnesota: water supply planning

During the subregional workshops, these best practices and recommendations emerged from stakeholder conversations in response to past and ongoing issues and present barriers. Overall, best practices work best when knowledge is shared and distributed between different jurisdictions, across agencies, and through communities.

These workshops presented an opportunity to coordinate efforts, prioritize issues among regional water supply leaders, and leverage partnerships between local water supply leaders, regional and state agencies. Future workshops should expand beyond water professionals and include economic development teams, land use planners, and community members in water supply planning. By allowing participants to engage with partners and share information, including the transparency of water management strategies and costs, the trust between partners is increased. Future workshops could also include trained facilitators, support from technical water professionals, and cultural knowledge holders to explain Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

A regionalized water supply and distribution for cities with limited financial and staffing resources may also help more rural communities by consolidating funds and staff. Coordinated data sharing on a regional level could allow for more robust groundwater models and economic development opportunities. If planned and coordinated with municipal water plans and groundwater models of available water supplies, new water users could be proactively recruited to areas that could support the water use. These partnerships could help fund water systems to operate and maintain municipal infrastructure. Additional economic revenue could also help support water efficiency programs and conservation programming for all residential, commercial and industrial water users.

Note: This information is part of a series of groundwater governance topics Freshwater explored during an 18-month project, which culminated in the report: Towards Collaborative and Equitable Groundwater Governance in EPA Region 5.