A friend and I took a long walk through Nerstrand Big Woods State Park on the last balmy weekend in December. The 2,884-acre forest straddles Prairie Creek, which is set deeply into farm fields in southeast Minnesota. The oasis of sugar maple, basswood, oak, hickory, aspen, elm, ash, and ironwood trees are a happy accident, kind of like the Lost Forty of virgin pines up north. So many families owned a sliver and used it for wood-lot, picnic, or hunting grounds that land buyers passed on it for being too complicated.

The fields that border the park drain into its steep, forested ravines. The initial land-clearing by settlers created a thick stack of black soil in the ravine bottoms; this is relocated topsoil, not doing much good where it is now.

This reminder of former farming practices is visible again because the newest export from fields to the park is water. A combination of wet years and the addition of tile drainage on fields—both conventional and organic—have increased flows into the park. Ravines have responded by lengthening, widening, and deepening. This explains why entire sections of trail have been washed away and toppled trees are common along ravines.

As we walked through the park we noticed FEMA-funded repairs stemming from a September 2016 rain event. Loads of crushed rock were dumped to fill gashes across the trails. Water was being directed by berms and new culverts were installed. It will take time for these to blend into the surroundings but a light snowfall was helping to mask them.

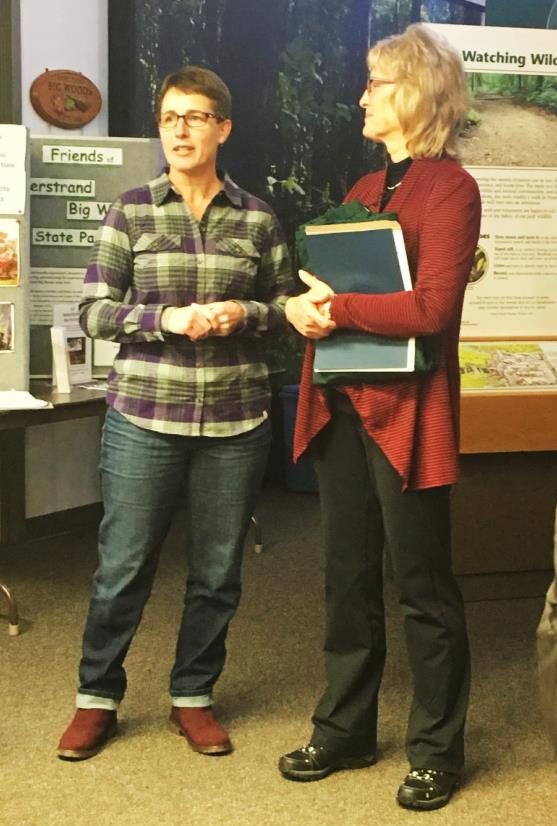

Retiring Park Director Elaine Feikema has witnessed a lot of change during her 12-year stint as park manager. The park has been plagued with erosion issues for at least a decade and she has commissioned more than a few scientific studies to understand all of the management challenges the park faces. “It’s complicated to make conclusions on environmental impacts over time in the Big Woods… Globally, climate change is a big factor … because these are rapid changes (relatively speaking) the landscape does not always adapt with rapid change.”

What should natural resource managers—and the rest of us—do when faced with rapid change? Elaine says that the volume and speed of the water that moves through Prairie Creek serve as reminders that we have very little control once processes are in play. We can best minimize the impact of hydrologic change rather than amplify it. Translating this strategy to the land around the park would mean finding a way to allow farmers to still farm, while minimizing downstream damage by finding new ways to hold back water and mimic the way it used to flow.

Elaine has learned so much but knows there is still a lot to do to preserve Nerstrand Big Woods State Park for future visitors. She is looking forward to working with the incoming park manager as a volunteer after her December 15 retirement.