Those April blizzards are a distant memory after spring whiplashed us into full-on summer in record time. The prairie we are restoring on our farm went from winter drab to black char to lush green in less than three weeks.

Minnesotans are beginning to understand how our water future is being impacted by a weakened and highly sinuous jet stream that sets up persistent weather patterns, letting Arctic air masses slip south and park over us. Dr. Jennifer Francis, our most recent Moos lecture series speaker spoke eloquently about this at the event and in an interview with Paul Huttner on Minnesota Public Radio’s Climate Cast.

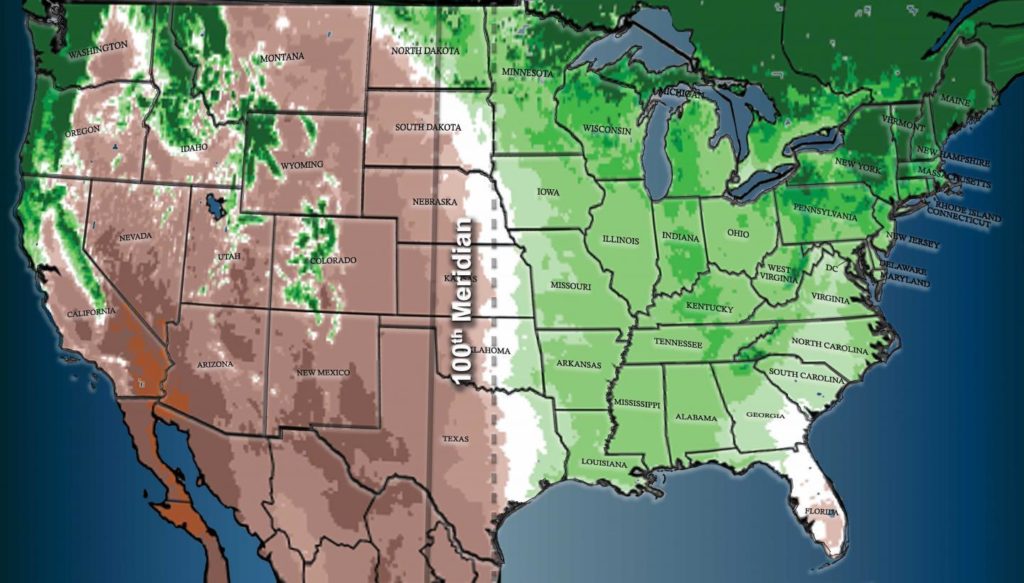

Have you ever looked west and seen the stark boundary between forest and grasslands and wondered why it was there or whether it was a permanent feature? This example of an ecotone – a region of transition between two biological communities – is so much a part of what we expect to see as we drive the interstates (a boreal forest up north, prairie out west, and a sliver of deciduous forest separating the two) that it’s even part of our state welcome sign.

Have you ever looked west and seen the stark boundary between forest and grasslands and wondered why it was there or whether it was a permanent feature? This example of an ecotone – a region of transition between two biological communities – is so much a part of what we expect to see as we drive the interstates (a boreal forest up north, prairie out west, and a sliver of deciduous forest separating the two) that it’s even part of our state welcome sign.

In fact, the grassland border has shifted 140 miles east in recent decades. The 100th Meridian bisecting the Dakotas is therefore no longer the easy rule of thumb for where dryness starts.

This is not a surprise to those who have studied the long record of climate in Minnesota. This ecotone moved as far east as Grantsburg, Wisconsin (take the Pine City exit on I-35, and keep driving east until you hit Wisconsin) and back again in the last 10,000 years. The entire headwater region of the Mississippi, including much of northern Aitkin County, was a dune field; Lake Winnibigoshish essentially dried up. Closer to home, sand swept across the entire Anoka sandplain, from Sherburne National Wildlife Refuge and Sand Dunes Forest across Carlos Avery Wildlife Management area to William O’Brien State Park, as lower water tables dried up the wetlands and lakes, allowing wind to blow the sandy soil away.

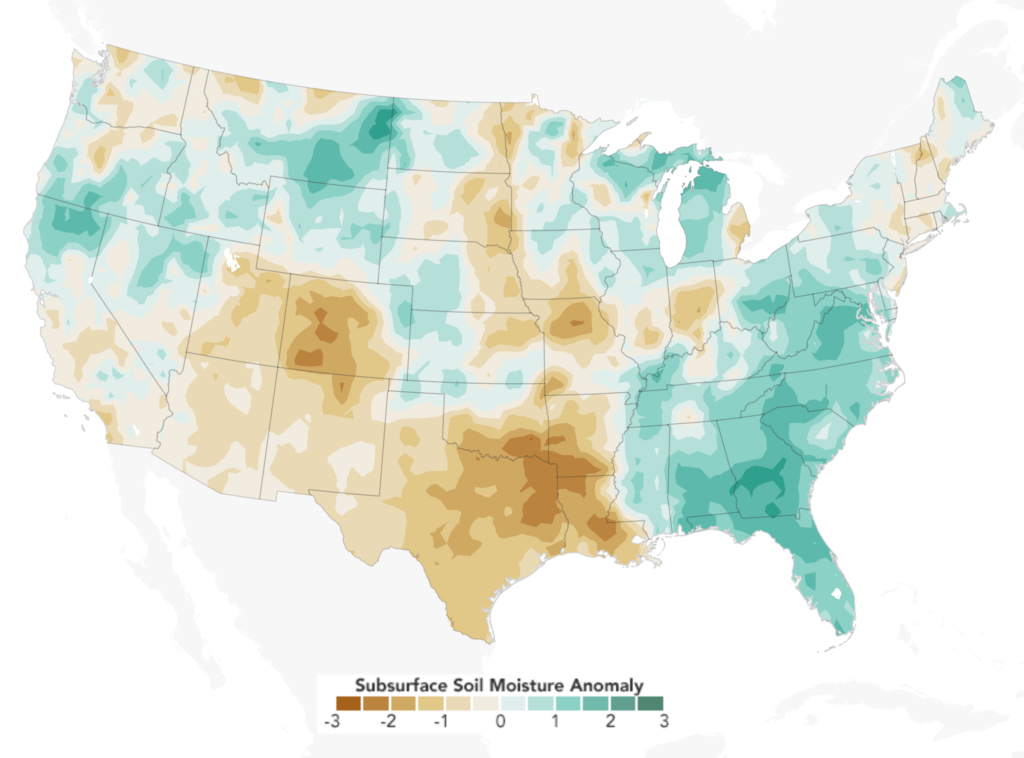

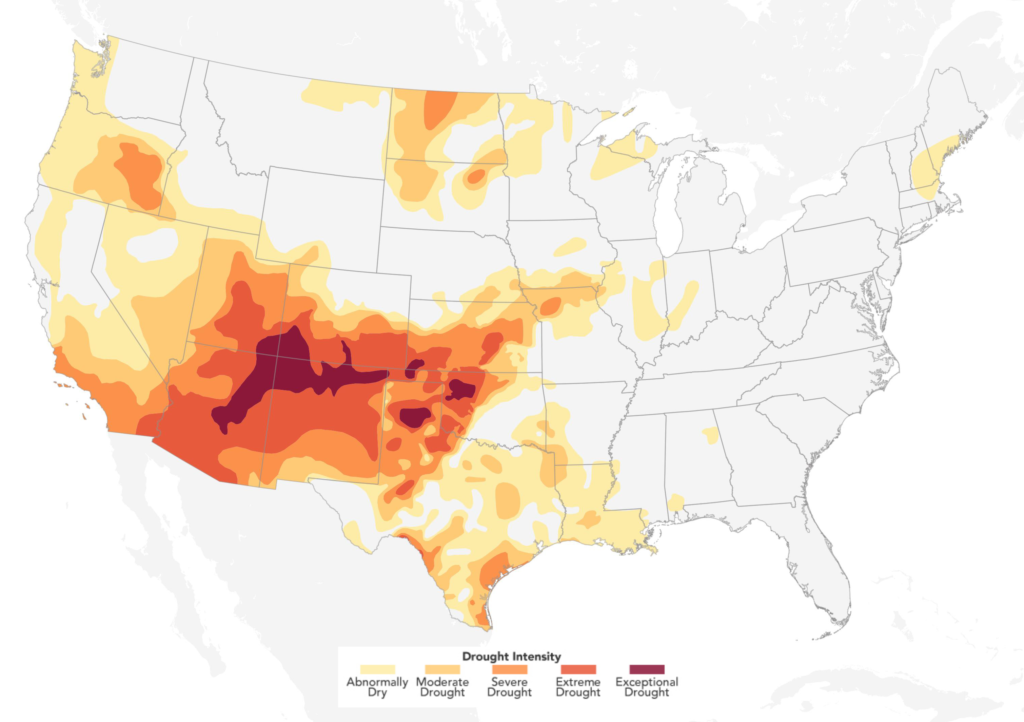

In the southwestern U.S., dry years have outnumbered wet years since 1999 and the NOAA Climate Prediction Center expects dryness to persist through the entire summer. Multi-decadal droughts are linked to sea surface temperatures known as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and have some thirsty westerners eyeing the Great Lakes.

https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=92274&src=eoa-iotd

Here at home, multi-year or decadal droughts may necessitate holistic changes to agriculture if and when drought returns, especially for those farms in the Pineland Sands, Bonanza Valley, and Little Rock Creek areas that already rely on irrigation to support crops on their sandy, drought-prone soils and lie near this eastward-moving ecotone boundary. Only about 15% of the total number of farms in Minnesota irrigate but concentrated areas of high capacity irrigation can mean groundwater is being used faster than it is being replenished. This can jeopardize the long-term use of groundwater for not only those farms and but also the economies of communities that share that water.

Drought-prone or sandy areas and those being converted to row crops for the first time are in need of data-supported planning efforts to ensure long-term, equitable use of the shared groundwater resource. With long-term drought at our doorstep, now is the prudent time to introduce irrigation efficiencies and conservation efforts. Look for specific recommendations in our recent report.

— Carrie Jennings, research and policy director