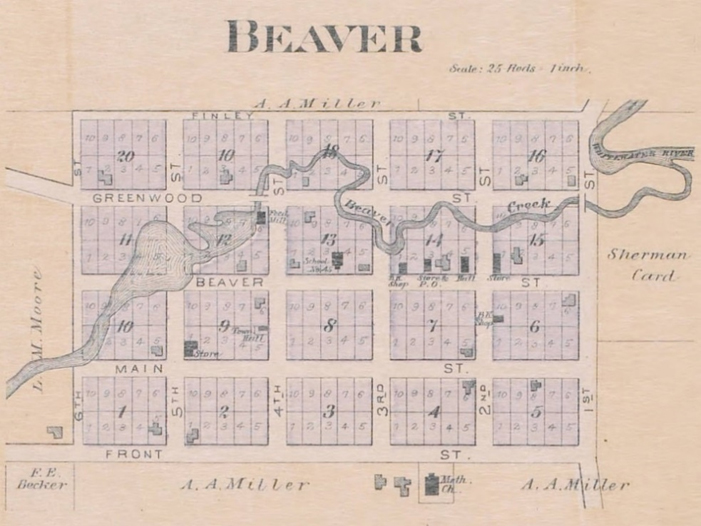

The town of Beaver in Winona County is a Minnesota ghost town. The Dust Bowl—the climate crisis of the decade—set the stage for the town’s demise. It was abandoned after being buried by silty topsoil.

Farmers of the day were locked into a style of deep plowing that resulted in fields vulnerable to wind erosion when dry dusty soil didn’t produce a crop. High winds blew the dusty soil as far east as Washington D.C. Locally, soil blew from the upland fields of Winona County and into the Beaver Creek valley, a tributary to the Whitewater River. There it was remobilized during the intense, infrequent downpours and created muddy torrents in the steep valleys that descend to the Mississippi River.

I have heard soil scientists repeat ghost stories of the first soil mappers who traversed southeastern Minnesota. They advanced, field by field, pushing their soil probes six feet into the ground, only to hit the tops of fence posts. To a soil scientist, this is akin to hitting a coffin with a soil probe.

In response to the crisis in Winona County, Minnesota created the first Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD) there in 1938.

Now there is an SWCD in every county. They are the source of trusted conservation advice and assistance to farmers who want to keep their soil productive and in place on their farms.

These days, a new climate threat is setting the stage for the next set of scary stories and Minnesota’s farmers are feeling similarly stuck in the face of it.

Intense rainfall events and increased precipitation overall across most of the state’s agricultural regions have changed farmers’ ability to plant and harvest in a timely fashion and has drowned out entire crops.

Tiling and ditching, practices designed to drain a field by hurrying the water off, is impacting downstream farmers. They are increasingly complaining about streams that are widening and eating away once-productive fields. In the Minnesota River watershed, 80 acres of farmland are lost to these hungry streams each year as “whole capes cake off in slices,” to quote Robert Frost.

Practices that were critical in keeping soil on the field during the Dust Bowl simply aren’t helping with the new reality of wet and wetter. Some of the solutions to prevent soil erosion might even be contributing by keeping fields soggy or by creating problems downstream.

So now is the time to pause and review the services and tools of our SWCDs in light of the current and future threats. Gov. Walz’s proposal to fund water storage in the Minnesota River watershed is in line with the kind of practices needed to restore balance. Retirement of marginal fields to store water will help everyone downstream. A well-funded, retooled, and revitalized SWCD in every county to implement these practices will serve us all.

One Step Backward Taken

Robert FrostNot only sands and gravels

Were once more on their travels,

But gulping muddy gallons

Great boulders off their balance

Bumped heads together dully

And started down the gully.

Whole capes caked off in slices.

I felt my standpoint shaken

In the universal crisis.

But with one step backward taken

I saved myself from going.

A world torn loose went by me.

Then the rain stopped and the blowing,

And the sun came out to dry me.

— Carrie Jennings, research and policy director

Nice “hook” ! An engaging way to build understanding and support for innovative water storage projects.